Creativity is not an internal light switch. It is not a clearly directable focus or endeavor; rather, it is a way of being. It is an organic living form, forever changing and responsive.

It is nearly impossible to articulate the vitality of artistic pursuit in a single definition – though Italian philosopher Federico Campagna might have come the closest. He named art as a prophetic endeavor– creation towards the “expression of the ineffable”.

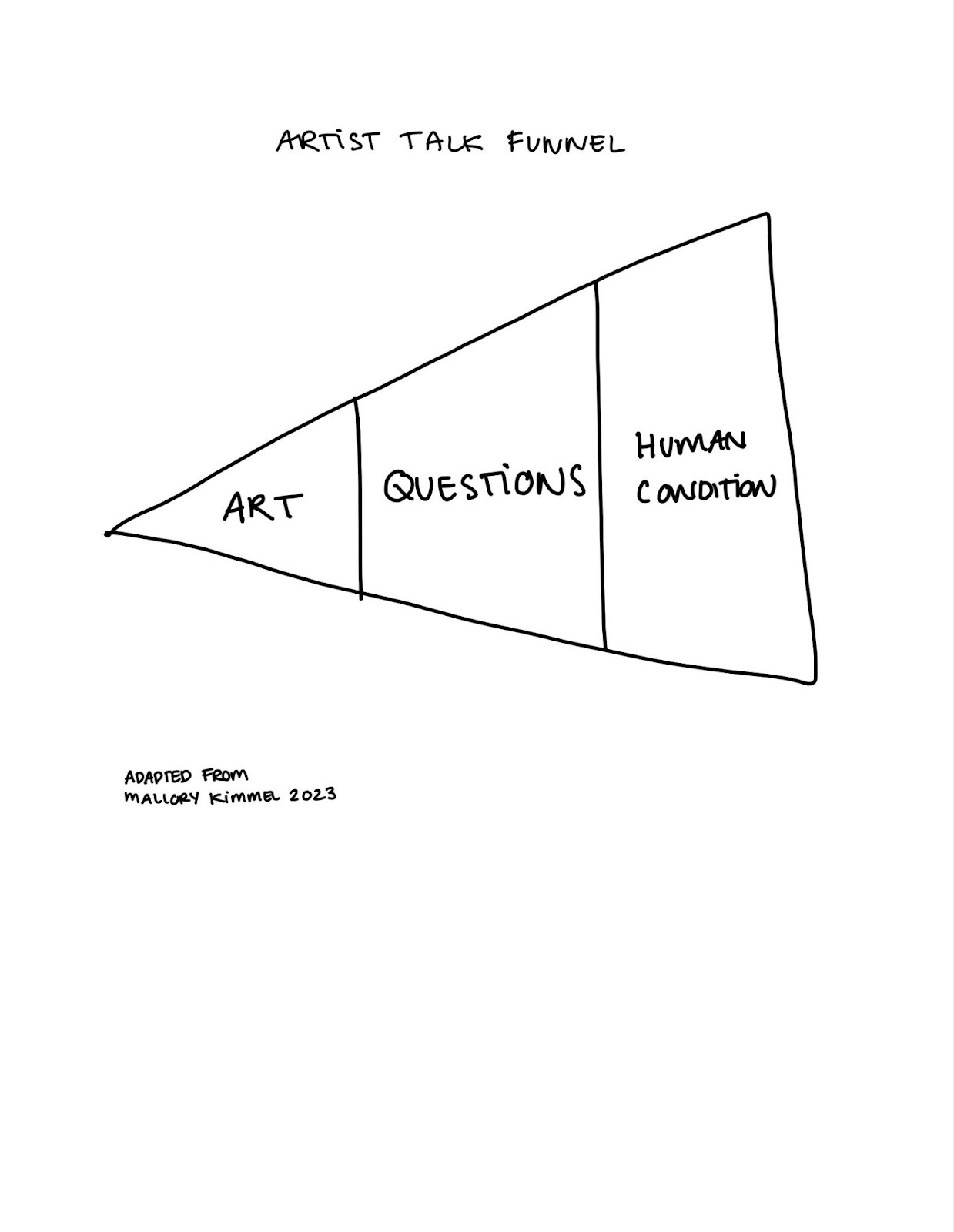

Art makes meaning in the space that words cannot, otherwise there would certainly be a lot more essays and even more readers. Campagna articulates the prophetic voice as one that speaks to a public, one that tells stories that inspires us towards building new futures, one that can simultaneously express what occurs between the present and past. A romantic and alluring suggestion, this is weighted by the reality of the conditions that surround a life dedicated to artistic practice.

There are an estimated 2.2 million graduates with arts degrees in the United States, many of whom have taken on serious debt in pursuit. Art schools are 7 of the 10 most expensive institutions in the US. This cost is amplified by graduate school; the average debt burden for a two-year MFA program is $93,000.

After and beyond their education, many artists pursue residencies, group studios, and work affiliated with institutions (museums, galleries, and/or academia) in order to continue their practice and stay connected with other artists and peers. If and when these opportunities are paid, the pay is scarce. It isn’t hard to deduce that lack of compensation often reserves many opportunities within this occupation for the very privileged, or those who can live under conditions of great scarcity.

The art market has never been simple (or kind), but it has become increasingly more complicated and untenable for working artists. In the face of a national recession, the gaps of Capitalism have grown more extreme. Smaller galleries have become rarities and long-term teaching contracts pretty much cease to exist. For better or worse, many institutions did not survive 2020. The consequence of the current conditions are now even fewer entry-points into the Art World, with more professionalized artists and less places for them to go.

The current drivers of such an inaccessible and burdensome art world require artists to rely on one another for visibility, access, and affirmation of their work; for mobility and survival. As artists, we need more supportive structures for art as an explorative endeavor, one that holds social progress over capital, one that is based on conversation and critique. Artist peer-groups inspire resilience and perseverance of this work in spite of less-than ideal conditions. Shared studios refine these practices through conversation and offer space in service of dedicated time. DIY project-spaces were birthed out of this need–some grew into larger institutions that are cherished and respected by their communities. Others have disappeared entirely; their traces all but forgotten.

Artist-led and artist-supported institutions often feel better for artists, which is why they are more likely to stick around and do the heavy lifting to keep them upright, or to at least tell their stories when they fall. Through shared language, experience, and working practices, spaces run by artists leave more room for the artist's ever-expanding conception of themselves.

At The Luminary, I met with thirteen studio members and volunteers from the arts advisory board in preparation for this exhibit to discuss their work. What was most striking about these visits is how each artist located the creation of their work as a process towards becoming something outside of themselves. While the subject matter, material, and lived experience of all vary greatly, each of them situates their studio activity as a form of research: a place to explore, express, and communicate their questions and findings about the world and their place in it.

ARTISTS AS HISTORIANS

ARTISTS AS RESEARCHERS

ARTISTS AS ARCHIVISTS

ARTISTS AS ACTIVATORS

ARTISTS AS CATALYSTS

ARTISTS AS HANDSHAKES

ARTISTS AS STORYTELLERS

ARTISTS AS MYSTICS

ARTISTS AS POETS

ARTISTS AS COMRADES

ARTISTS AS ORGANIZERS

ARTISTS AS BUILDERS

ARTISTS AS SUSTAINERS

ARTISTS AS SCIENTISTS

ARTISTS AS DREAMERS

ARTISTS AS QUESTIONERS

ARTISTS AS CRITICS

ARTISTS AS ________.

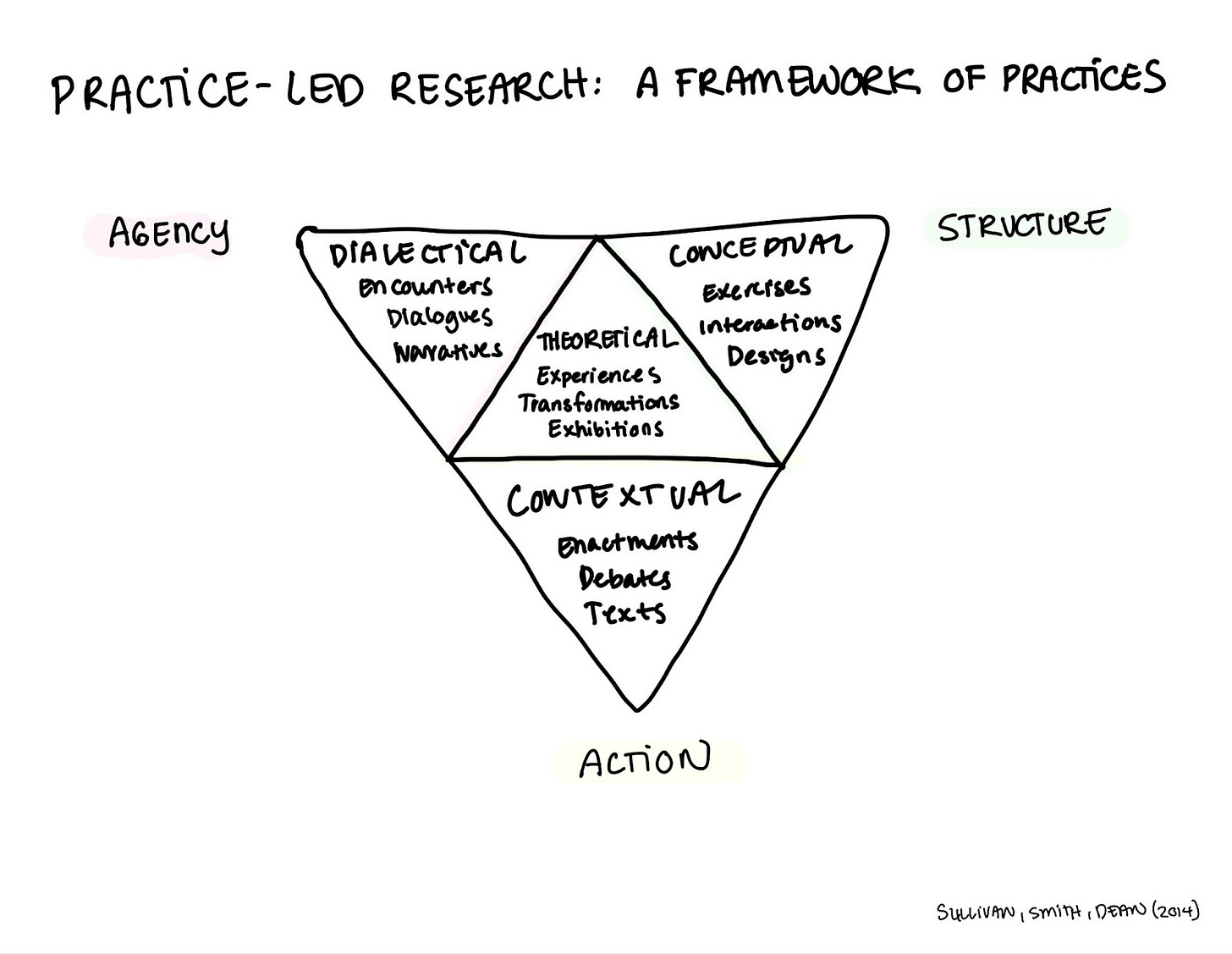

The theoretical form (see figure below) of making meaning is the heart of practice that all artist-researchers operate from, the process that works to make sense out of information so it can be translated or communicated to others. The theoretical center is fostered as a creative origin where problems are located and then explored across other modes. This initial approach is one of sensitivity to serendipity and innovation. Artistic research then floats across an array of possible outcomes, with a variation of structure, action, and agency in their effect.

For many artists I met with this is deeply material; this practice is explored as a way of giving form to thought, making meaning out of what we already know, collecting data to create data. This mode is considered to be conceptual, and I find this to be the lens under which artists are most comfortable locating their practice. Some artists make meaning out of experiences that are felt, reconstructed, or interpreted– whether these are public or held in the studio. This framework is considered to be dialectical in practice. Contextual practices involve thinking in a setting, often affiliated with critical exploration around social issues that are local in focus but global in reach. Arts writing, creative pedagogy, and critique are some easy examples of contextual practices.

Integral to knowledge production led by practice is a willingness to leap into the unknown. We do so in order to know. The result of this work does not have to produce entirely new logic, but provide a reflexive exchange between artist and viewer mediated by the artwork. Practice-led research is a framework of cultural reciprocity; it’s how artists explore, express, and communicate their point of view in relation to ideas and affect.

Amplified through advocacy in the conceptual and postmodern eras, creative practices became rationalized as a form of academic research because of their unique contribution to the generation of new knowledge, particularly in the humanities and social sciences. As a result, research-led artistic practices gained some economic empowerment through institutional accreditation. The practice-led pursuit is now regulated and dulled in consequence; policies and procedures are implemented which dictate how research can be conducted and what is considered adequate or competitive knowledge in the intellectual marketplace. Ultimately, these institutions manufacture and guide what projects are funded, published, and sustained. One can also trace a suspect correlation between this expanded definition of practice within academia and the increase in the MFA-debt crisis...creating situations of perpetual entrapment. Ironically, despite their integration, creative research methodology remains at odds with scientific methodologies even when housed in the same spaces.Often, outputs informed by STEM methodologies are given preference over creative frameworks. This is why a graduate thesis project for art-students is often a highly stressful experience. It is the process of mapping a constellation into a line.

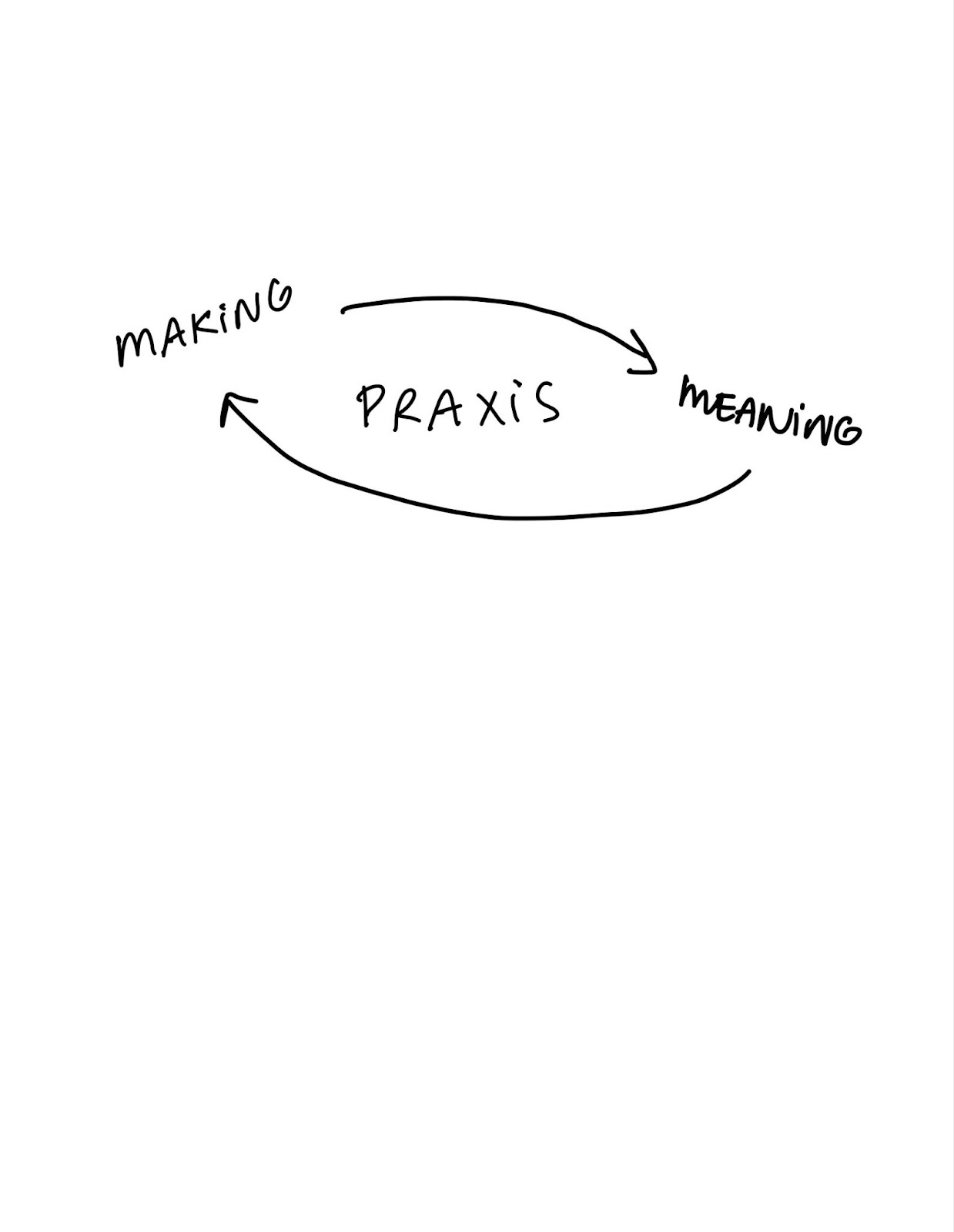

If we were to truly embrace practice-led research as a valuable form of knowledge production, we must embrace praxis: the mode of making to find the idea to find the meaning to then inform the making again. It is a modality of exchange, chance, risk, failure, commitment, trust, and introspection. Praxis asks a lot of our artists. When understood, it is something we can use to guide not just how we engage artwork, but with each other.

In acknowledging the broader process of forming knowledge as valuable labor, we must recognize that it is being conducted everywhere, not just within the larger institutions. As a leader of an arts organization I ask myself: what measures will protect this labor as it occurs in spaces closer to the margins? What visibility is safe and supportive for the underground? What are the strategies for mobilization, access, and survival in these spaces? When is the research performed in them valuable? Who gets to decide that?

Building an artist-centered art-world is a good first step.. In the spirit of practice-led research, building an institution that is artist-centered means upholding praxis. We embrace what we know and prepare for what we will find out along the way. Our way of operating may come with frustration as we confront a world that is not structurally prepared for us. But, through a process of shared intentionality, we might find a way through that is reciprocal. Our path of praxis acknowledges labor and its production. It speaks to something ineffable in all of us. That is my hope and what I am in service of.

Sources

Note from journal in response to a video interview with Ann Hamilton

Federico Campagna: Prophetic Culture: Recreation For Adolescents

BfaMfaPhD: Artists Report Back 2014

DATA USA: Visual and Performing Arts Tuition in the United States

Hazel T. Smith & Roger Dean: Research-led practice, practice led research in the creative arts

Mallory Kimmel: Gathering Together, as Ourselves, as One

Institutions by Artists: Volume One

The creative practices and contributions of: Heather Bennett, Grant Benoit, Emma Bright, Vaughn Davis Jr., Jessie Donovan, Kalven Duncan, Kevin Harris, Macayli Hausmann, Brian Lathan, Hayveyah McGowan, Dr. Bill Russell, Jen Wohlner, Kellen Wright.